Jonathan Yeo: Exploring Visual Extremes

Like Francis Bacon, who always felt lucky that he never received any art training, Jonathan Yeo is entirely self-taught. So he could opt for portraiture without expecting his art college tutors and fellow students to mock him. The whole notion of painting portraits was, after all, regarded by many modernists as irredeemably old-fashioned. But Yeo had become obsessed by portraiture at an early age, making caricatures of his teachers at school and then drawing them seriously in order to achieve a ‘likeness’. He still gains immense stimulus from looking at, and learning from, portraits by great artists of the past. At the same time, though, he has no intention of confining himself to an unadventurous, formulaic approach.

For Yeo, contemporary portraiture is essentially a challenge and it relates to a tradition that embraces some of the most outstanding British painters working in the twentieth century. Stanley Spencer was able to concentrate on a very closely observed and incisive definition, while at the same time taking audacious risks like juxtaposing his naked body and his wife’s with a leg of mutton. David Bomberg, Spencer’s contemporary at the Slade School of Art, stimulated Yeo in a different way. He relished Bomberg’s far looser late style, which was more sensuous and above all open to the vivacity inherent in his subject. Bomberg claimed that he was searching for ‘the spirit in the mass’, but Yeo also found inspiration in Wyndham Lewis’ hard-edged precision, with its emphasis on the enduring importance of line. Lucian Freud’s prodigious ability to renew this portrait tradition, taking it forward into the twenty-first century, likewise impressed Yeo.

The freedom Yeo enjoys when committing himself to the act of painting people can be appreciated very dramatically in his recent images of Cara Delevingne. When he first invited her to come round to his London studio, about two years ago, Delevingne was known principally as a fashion model, but has since moved further into the world of acting. One thing that has not changed in that time, though, is her extra-ordinary mass appeal, seen in her army of followers on social media.

Right from the outset, Yeo realised that she was extremely energetic. ‘Like many people Cara doesn’t sit still’, he says. ‘Sitters can often feel self-conscious when they start coming to the studio, but Cara likes playing around. She can be herself, a performer or a clown, so I was able to experiment with more unorthodox ideas from the start.’ Yeo does not need people to sit dutifully in front of him all the time, and Delevingne’s vitality encouraged him to explore a number of approaches across several canvases. ‘Most portrait exhibitions are filled with portraits of different people all done in the same way, but how about one person done in different ways?’

This was the challenge he had already set himself by painting Kevin Spacey, and the variety of the results was enhanced by Yeo’s decision to portray Spacey in character: firstly as Richard III, and more recently as Frank Underwood from House of Cards, not to mention Clarence Darrow, which was Spacey’s final role on stage at the Old Vic. But Yeo went even further when Delevingne started invading his studio. Early on, he painted a full-length portrait of her wearing a pair of vintage telescopic goggles that, according to Yeo, ‘serve partly as a device to suggest there’s something interesting going on outside our field of view, and partly as a prop that obscures part of her face. I often use objects to highlight my subjects’ identity but here I was using one to subvert this process of recognition’.

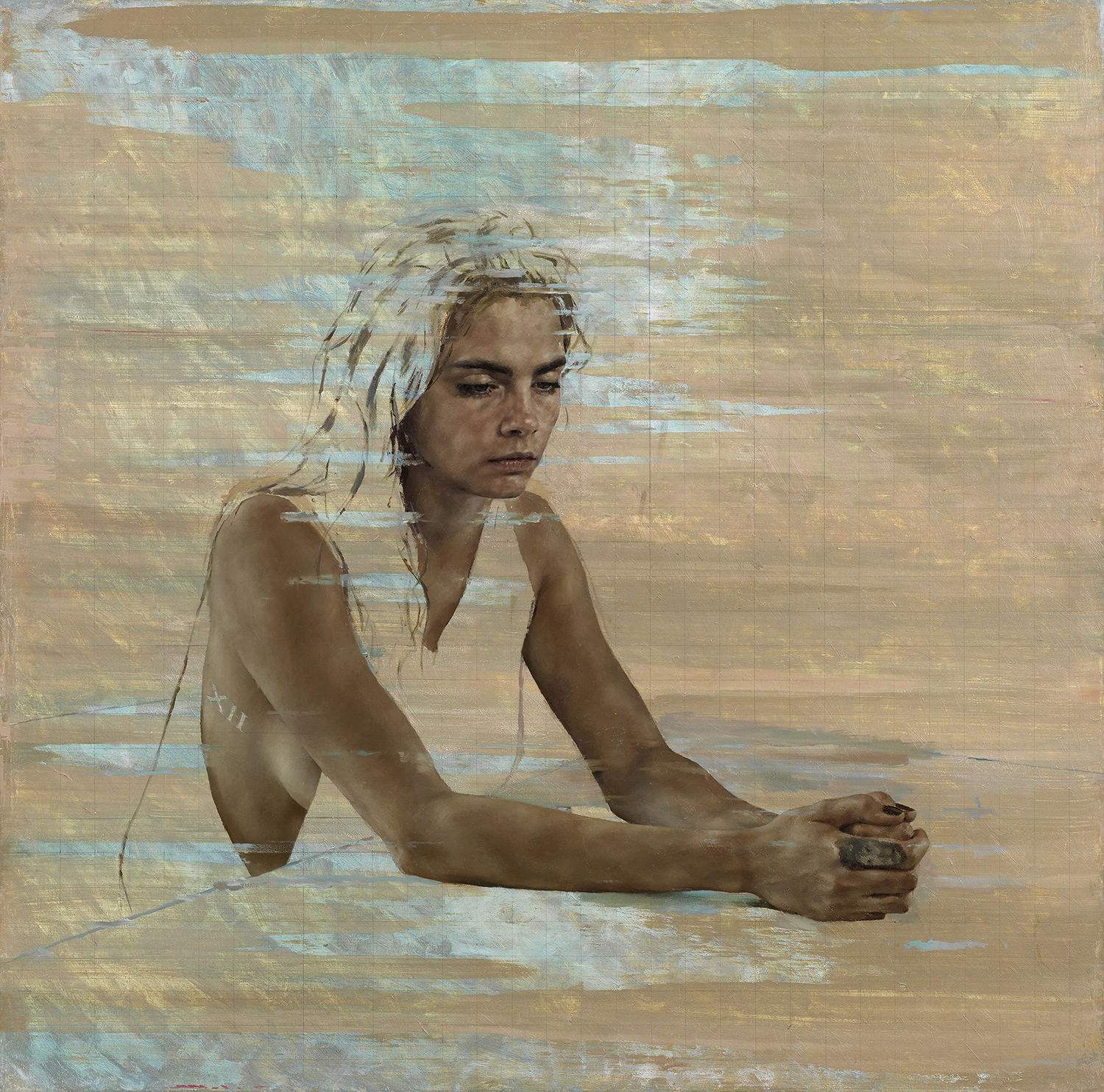

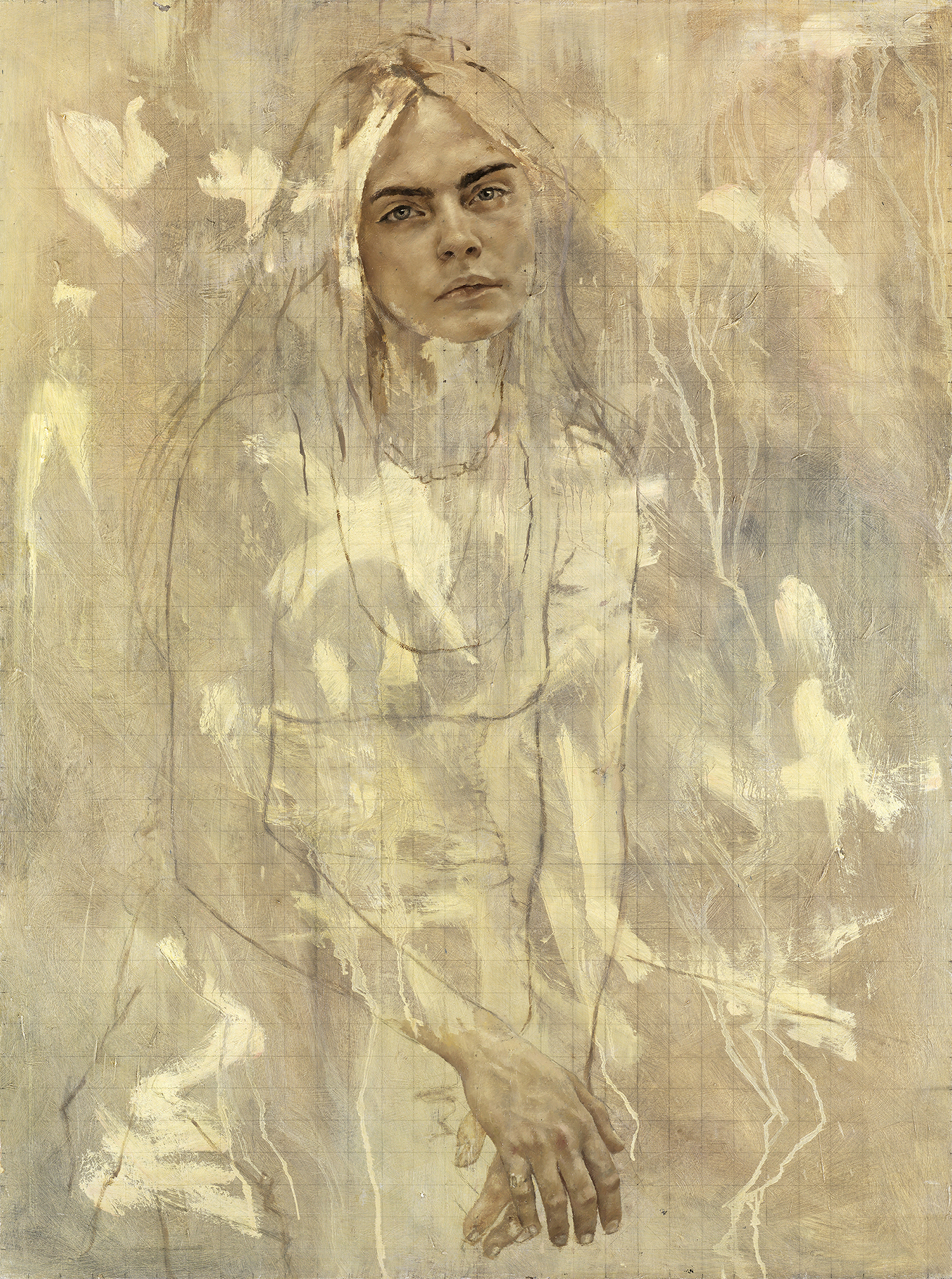

‘I wanted to explore the contradiction in Cara between the vulnerable and the extrovert’, he explains. ‘Cara is constantly seeing her life caught in highly polished photographs, and she often deals with that image by being playful: crossing her eyes, sticking out her tongue, not taking herself very seriously.’ Hence the central tension in Yeo’s portraits of Delevingne between finish and lack of finish. ‘I like elements of abstraction and uncertainty: it’s never resolved, and photography is not how we see things. I want to get closer to how we remember an image. Slight abstraction, I believe, is more real than total realism, and I want this to come out through my work. We receive too much visual information now, so we actually need to restrict the information and make it more mysterious.’

Yeo became willing to take extraordinary risks in his subsequent portraits of Delevingne. He realised that ‘She’s got such a recognisable face, and most images of her are keen to exploit that, but it seemed interesting to see how much you could obscure it and still convey her presence’. He even went as far as to paint her wearing a gas mask, staring out from an expanse of freely splashed whiteness with a sinister dark tube dangling down into the void. We cannot see her eyes, even though Yeo acknowledges that ‘Cara’s eyes are so interesting: she always looks as if something very interesting is about to happen, even if nothing is happening at all. It’s very hard for her to look bored.’

Yeo responds in particular to Delevingne’s restlessness. ‘Cara throws herself into things’, he says with enthusiasm, and this aspect of her personality doubtless encouraged him to make a much larger painting of her wearing enormous optometrist’s spectacles. She is gazing towards an image of herself on an iPhone. So, on one level, Yeo is here defining ‘the moment of the Selfie’, but the full meaning of this picture embraces other considerations as well. An optometer is an instrument for testing the refractive power and visual range of our eyes. So the capability of human vision is emphasised here as much as the technology of the iPhone. Yeo is acutely conscious that, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, ‘the number of photographs we’re taking and showing on social media is more than doubling every year. A vast proportion of these are self-portrait images’. That is why he is at pains to stress that ‘the way we see is very different from the way a camera sees’.

Yeo insists on using his paintings to explore compelling contrasts between visual extremes. In the painting where Delevingne is wearing optometrist’s spectacles, her face and fingers are depicted with well-developed clarity. But most of the canvas looks almost ghostly, as if Yeo is about to leave figurative precision behind and wander off into a more dream-like world. The contrast vividly expresses his belief that, ‘as human beings, we read faces more intensely than anything else: this helps us to decide, for example, whether someone is a friend or foe. That’s why the face has to be the first thing you notice in the paintings.’

Committed to trenchancy rather than blandness, Yeo wants to redefine the world around him. While ‘playing with the negative space’ in his paintings, he also uses the multitude of electric lights carefully assembled in his studio to ‘heighten the three-dimensionality of his subjects’. He is pushing himself towards using picture surfaces far larger than before, and one of these unprecedentedly monumental paintings is dominated by a split image of Delevingne’s head. Half her face is defined in a well-developed way, so that we feel confronted by her solid presence. Yet the other half is reflected within a mirror held in her hand, so our eyes continually move from one to the other.

This duality must surely reflect Yeo’s fundamental awareness that there can be no such thing as a definitive portrait of Delevingne: ‘I was playing with the notion that ideal beauty requires a perfectly symmetrical face, which none of us actually have. It also references the role of the performer in reflecting a version of reality whether they are wearing actual masks or not.’ But perhaps the most astonishing of these portraits shows Delevingne wearing a comedy Groucho Marx disguise, with a large bulbous nose, bushy moustache, big spectacles and thick black eyebrows. ‘Being an actor means being in the deception business’, Yeo explains. ‘So many people project themselves through social media now, sharing self-portrait images on a daily basis, and Cara is one of the people at the forefront of this visual revolution.’ That is why Yeo has become fascinated by the idea of encompassing such a complex variety of guises, and he aims to convey it with the maximum amount of perceptive conviction.