under the skin of jonathan yeo: an interview

Sarah Howgate is the curator of contemporary portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in London. This interview took place in the months leading up to Jonathan's 2013 display at the NPG, Jonathan Yeo Portraits.

The text is also included in the 2013 monograph The Many Faces of Jonathan Yeo, published by Art/Books.

SARAH HOWGATE: Let’s start by talking about how you became an artist. You are very successful but completely self-taught. How and why did that happen?

JONATHAN YEO: It’s a combination of things. I had always liked the idea of making art from a very early age. But it was never even remotely presented to me as a possibility for a serious career. If anything, the reverse was the case. When I was at school, which was a slightly obsessively academic place, art was seen as a last resort, something that you did if all else failed. But I loved it – I just always thought it would be nothing more than a hobby.

SG: And why, when you eventually became a professional painter, did you choose portrait work?

JY: I’ve always been drawn to portraits more than anything else. My favourite work by an artist is always their portraits, whether they are known for making them or not. And also I do find it relatively easy to get a likeness of a person, partly because I used to sit and doodle people’s faces in the back of lessons at school. At the same time, I knew that many other artists had been put off portraiture because it was outmoded. Lucian Freud was one of the most significant figurative artists of the last fifty years, but not that long ago he was considered anachronistic. Even in the 1980s, when I started working, he was still a divisive figure. And a decade before that, he was seen as being totally backward-looking.

But I think I was lucky that I went into something that was very out of fashion. You can succeed more easily at something if you go into an area that a lot of other people aren’t attempting. In any case, the rules get rewritten in all walks of life all of the time, and that is particularly so in the art world. It is extremely susceptible to fashions. It used to be very difficult to do figurative painting and be taken seriously. It’s almost the other way around now.

SG: You take on quite a number of commissions today, but presumably you did more when you were starting out, in order to earn a living?

JY: I assumed early on that I would accept commissions only for as long as I had to. In fact, I thought I would do portraits only for as long as I had to. I wanted to do other things. It was only when I went on a holiday when I was about twenty-seven and had made a bit of money that I thought, ‘Right, I’m going to take a month off and travel.’ After less than a week, I was back to getting my friends to sit still so I could paint them. I was trying to find out what I really liked doing and it took me just a few more days to understand that this was it.

Sometimes it’s tempting to take on a commission because there’s a lot of money in it or because it seems very glamorous or it’s likely to open the door to something interesting. But unless the chemistry between myself and the sitter is there, it’s usually a mistake to do it, because you just end up spending too long on it and hating it.

SG: Does it matter to you what the subject thinks about the portrait? David Hockney and Lucian Freud used to say that they didn’t care – that it’s irrelevant to them what the sitter thinks.

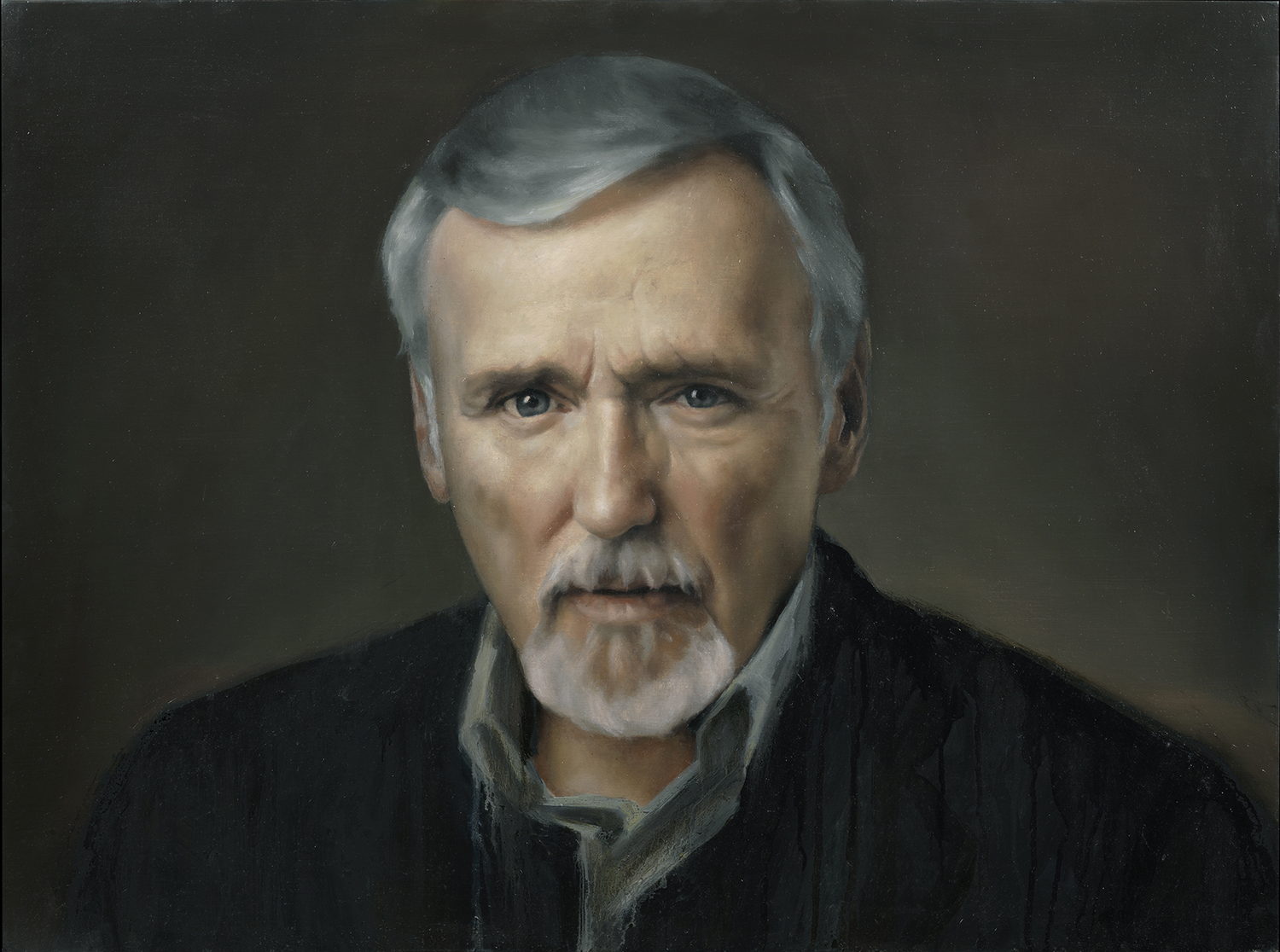

JY: I think artists feel that they have to say that. The honest answer is that it depends on who it is. I remember with Dennis Hopper, I wanted him to like the portrait because I respected him as an artist and as a viewer. He was much more knowledgeable than me about twentieth-century art and about different ways of looking at things. Not to mention that, being an actor, he was so aware of the power of his own image.

SG: The Hopper portrait, in particular, has a lot of references to Old Master paintings: the dramatic lighting, the black background. Was that conscious?

JY: It was. He came to the studio dressed like that. Every actor I know is highly aware of what they’re showing you. When he saw the portrait, he didn’t like it, but that may have been because I first showed it to him by email, which doesn’t present things very well, because it’s a photograph, pixelated and much too small. Secondly, I’d done an earlier study – a much looser study – which he had loved. I made the mistake of sending that to him beforehand, so he thought the finished painting was going to be a bigger version of that.

So in the end, he came to the studio and I painted another looser portrait. He said he wanted the study as well, so I gave that to him, and kept the Old Master version. When he came to the studio and saw the original portrait, he asked, ‘Oh, is this the same one? It looks very different and I like this one. Can we swap?’ I said ‘No way!’

It is important not to be too worried whether the subject likes it or not because they’re only one person, and quite often if they like or dislike what you’ve done, it is because of something completely irrelevant about their appearance. I may have made them look slightly older than they were expecting, or slightly fatter than they feel. Or they might be just hung up about some detail of their clothing or jewellery. So I know what Hockney and Freud are saying, and I think that they are right. It is difficult not to care at all, but certainly there aren’t many situations where there’s really any advantage in caring.

In any case, generally sitters don’t know what they look like. Sometimes a sitter doesn’t like to see themselves or their partner looking a bit older than they were hoping, but they hardly ever disagree with it. Then again, they probably wouldn’t sit for a portrait unless they had thought about how they looked. On the whole, the people I paint have a very high level of self-awareness, even if it’s a slightly romanticised or slightly vain version, but it’s often much less of a problem than you would think. It’s those who know the sitter well who are better judges of whether you’ve succeeded at getting the personality and persona right.

But fast forward ten years and it doesn’t matter. When you look at any of the great portraits from history, do you think, ‘Oh, let’s do the math about how old he must have been at this time: was he looking good or bad for thirty-five?’ You don’t think like that. It’s about how you read the subject’s personality. And if you’ve known someone for only ten minutes you can’t really know what is genuine either.

That’s why to do a portrait I find it crucial to see people on several different days. It doesn’t matter if you don’t see them for very long, but I still think you get a better overall picture of someone if you see them over time. Even if you get someone sitting there motionless one day and animated the next, people are never the same. Also they tend to change after the first time you meet them. Lots of things evolve over the course of the sittings.

SG: How important to you is photography in your process?

JY: I’ve worked entirely from life at times and entirely from photographs at others; each approach has its limitations. What I do currently is to use both. I tend to start off with photographs, partly because you’re looking for that sparky moment when someone is not being conscious of being looked at. So it’s not the first photo you take but probably the two hundredth, when they’re getting bored of it. I then use a combination of photographs to start the initial process of composition and to get a sense of the layout. But then at some point you need to let the experience of them and the sight of them on different days take over. There’s no hard-and-fast rule about it.

My mum was a keen photographer, and I would be in the darkroom with her as a kid. I love the magic of the process and all the different ways of using it, learning about things like the shallow tonal range of photography, that things go from light to dark very fast, and that the camera doesn’t see things in the way that we do. Lighting is really important if you’re going to use photography as a painting tool. You’ve got to learn how to light things, really plan it out and not just rely on chance. Also, you’ve got to be very aware of its limitations. There was a time about ten years ago when lots of people were doing photorealist paintings. You’d have people who were technically good at painting, but painting from some really bad photographs. It was a weird thing to look at because you were getting the worst of both worlds.

I think it has got better recently but I still think that you should be honest about it if you’re doing something one way or the other. At the moment, I’m using photography a lot of the time. Having said that, I’ve also done two or three portraits recently where I haven’t used photographs at all, but those have been people who have written about my work and I know well, such as Giles Coren, Philip Mould and Martin Gayford. I like it when I know someone well. It doesn’t take ten sessions; I can do it in two. When you paint from life, you get energy, and you also get things done fast.

You don’t plan the composition so well, but that’s something I’ve honed over the years and tried to use in a particular way. It’s more fun painting from life because people like seeing something develop. I think for people who can’t do it, it is a bit like being a conjurer, being able to produce an image out of nothing in a short space of time. So it makes for a more enjoyable way to spend your day.

SG: I want to talk about some of the other subjects in the exhibition. You’ve painted some of our most prominent artists, not least Damien Hirst and Grayson Perry. Thinking about Damien now, how was it to paint the former enfant terrible of the art world, and why do you think he agreed to sit for you when he had never sat for anyone before?

JY: He might be at a slightly more reflective point in his life. That’s often the case with people who sit for a portrait. He’s also probably achieved most of the things he ever set out to achieve, and so he’s not quite so frantically busy racing around the world trying to get his work seen. He seems in a good place at the moment actually, and he’s fantastic company.

SG: Is he more contemplative, perhaps, now he has reached middle age?

JY: Yes, I think he is. That happens. It’s funny with portraits, it’s not always obvious at the time, but when people decide to have their portrait painted, it’s often at a time of big change in their life. It’s a time when careers change, partners change – it’s a time of reassessment.

Damien has always been generous spirited. He didn’t just buy my work; he bought work by loads of artists. Sometimes he’s done it wisely as a good investment, and other times I think it was just to be supportive. He’s very supportive of other artists. But I do feel more pressure painting another artist.

It was the same with Grayson. They may do very different work, but you feel that these are people who spend so much time thinking about things that are similar to what you do. You are aware that they may test you and want to know why you’ve made certain decisions. So of all the people I’ve painted, I felt more pressure with those two, I think, than with almost anyone else.

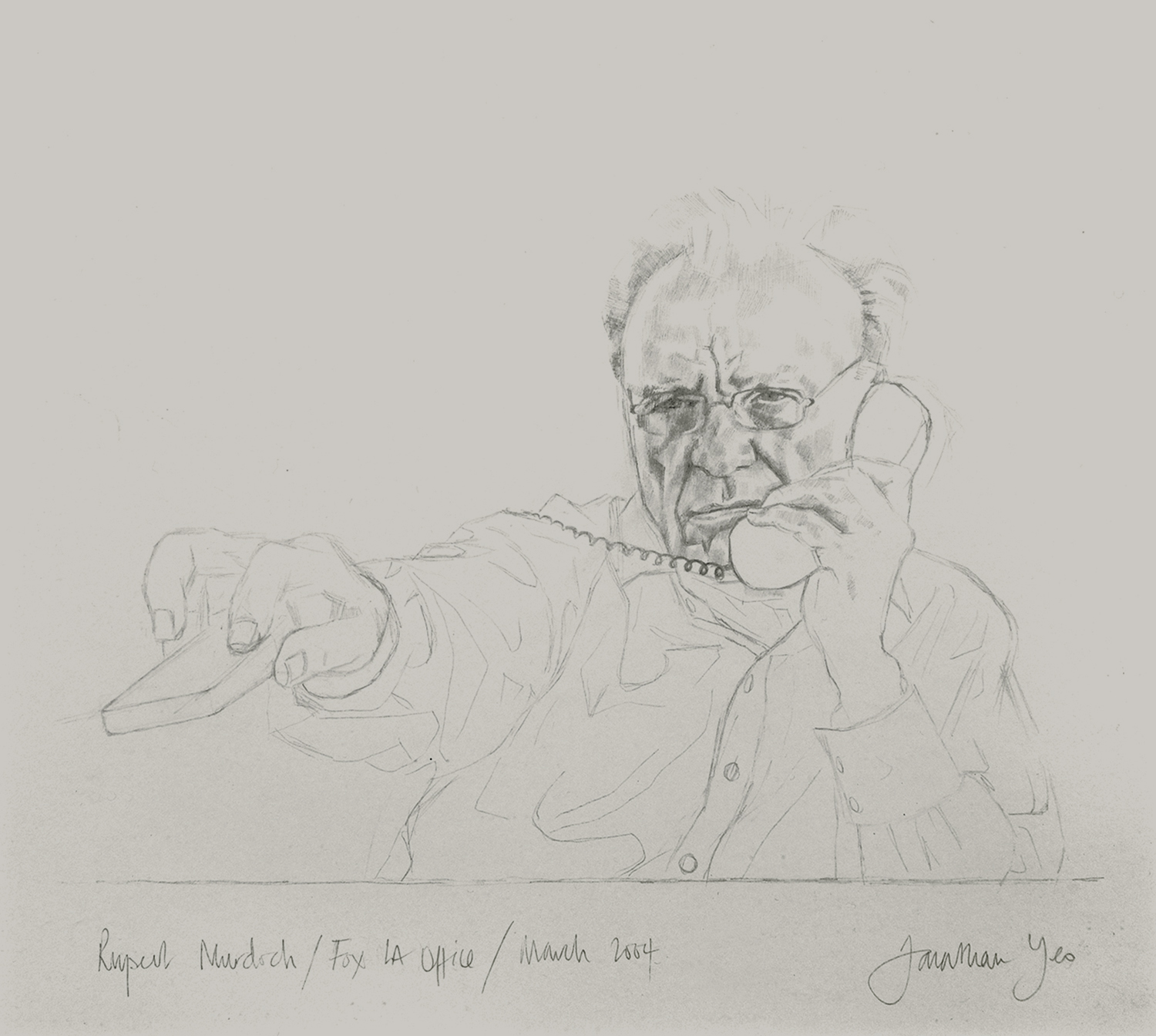

SG: We are all very familiar with Rupert Murdoch from our television screens and newspapers. But for him to sit for quite a formal portrait must have been strange and intimate.

JY: He has become better known to the wider world very recently, of course, but when we were doing the portrait, eight or nine years ago, he was known mainly to people who read Private Eye and the Guardian and who keep up with what’s going on in the media; he wasn’t as familiar as he is now.

What interested me about painting him was the way it showed the relevance of portraiture. He’s never been interviewed by Jeremy Paxman on Newsnight. He wasn’t a politician who had to be seen to answer questions or to justify things. He was in the shadows, he was an unknown quantity, and I think that’s why some people were afraid of him. But that made him very interesting because he’s clearly an important cultural figure. He has accelerated the process of change in all kinds of things.

Whether one agrees with those changes or not, he’s definitely been an agent of evolution in society. Therefore he is someone we should know about, and a portrait is a way of finding out things about a person. Inevitably, what you discover is that he or she is nothing like what you expect. Murdoch was endlessly fascinating to talk to, but it was also quite hard work because I always felt that he could run out of patience with me at any minute.

SG: So you talked when you were painting him, which I presume you prefer not to do?

JY: He was very busy and so it started with my going to him and sitting in his office and just sketching and taking photos. I was observing him, sometimes he was talking to me but mostly he was talking on the phone. But that was good because he quickly ignored that I was there. Then, as the portrait progressed, he came to the studio. You want to see people talking a bit of the time, because that’s what you can’t get from photographs or anything else – you have to witness that.

SG: But you prefer not to have to respond, ideally?

JY: Many years ago, I painted Peter Bazalgette, who started off making reality programmes and documentaries. He’s a very wise and experienced old television hand. He said, after a couple of sittings,

‘You know, you do something that we try and teach our young interviewers to do?’ ‘What do you mean?’ I thought he was accusing me of a sort of trickery.

He said, ‘I don’t think you’re even aware of it, but you ask a question and people start responding, and instead of making the mistake that most people make which is to say “Oh, that’s interesting, yes, do tell me more”, which of course stops people from talking, you just smile and nod and don’t say anything at all; just raise your eyebrow, look very interested and nod.’

It’s a way of coaxing people into talking. They hate the silence, so they want to fill it. The reason I was doing it was because I’d unconsciously learnt this way of getting people to talk so I could think about the painting and not to have to engage in conversation.

SG: You’ve painted a lot of subjects who are used to being in the driving seat. Michael Parkinson, for instance, is well known for interviewing people and he’s actually in the opposite seat, isn’t he, in the portrait? I wonder how he took to being, not exactly interviewed, but painted.

JY: I think he was certainly interested in the process. Michael started off as a journalist and what you realise quite quickly is that he’s got this wonderful, easy-going manner and he’s utterly courteous and seems completely sweet-natured and straightforward. He is one of the loveliest people you could ever meet, but he also has the mind of a highly intelligent and sharp journalist who remembers stuff. He’s done his research. He’s read about people, he’s formed opinions about them. He’s got this wide experience and knowledge of other similar situations to call on. To subject himself to the same scrutiny that he has imposed on other people is a way of reflecting on what he does.

SG: When I look at your portraits, I am struck by how some of them have a distinctive unfinished quality. I’m often reminded of the portrait of William Wilberforce by Sir Thomas Lawrence in the National Portrait Gallery collection. Has that painting influenced you?

JY: I think that is one that I remember from when I was younger. Not because of its subject, but because of the aesthetic. I liked the sense that Lawrence had done enough and just left it. The thing I don’t like is when artists plan something to look unfinished. There is something phoney about it that I think you have a sense of even if it’s not obvious – that artfully unfinished look.

The best unfinished portraits I’ve done are ones where I planned to do the whole thing and then find there’s a point where I happen to come into the studio one morning and wherever I had left it the night before just works. Or I find myself going too far and then rubbing it back a bit.

The portrait of my wife Shebah was one example where I had intended to do a lot more and left it one evening, came in the next morning and liked it as it was. It’s the economy of detail, I think, and that’s something that works particularly with portraiture. There is a finite amount of information you’re trying to get across in all that and yet you’re trying to convey various aspects of someone’s personality, at least as much as you know of it.

The portrait of Grayson Perry is one where I painted the whole thing in, hated it, and started rubbing it all off. Then I thought I’ll just do the background first and the sort of ribbons. Then that was okay and so I left it for a few days, and my friend Charlie came in and said, ‘That’s the best one you’ve done!’ Typical dealer! But actually, he wasn’t wrong.

SG: How do you equate that with your portraits of people like Erin O’Connor, for instance, a model who has this flawless face? Is it hard to get under the skin of someone like her who has that perfect image?

JY: The picture of her that was in the BP Portrait Award exhibition in 2005 was really a study I was doing while I was getting used to her in my mind and trying to figure out what to do with the actual portrait. I liked the proportions. I’d been to see her in New York and had done some sketches and taken some photos of her.

She’s an actress really; a very clever one. And with her, you’re also dealing with someone who has had a million photographs taken of her, so she is very aware of how she looks. You’re not going to have to suddenly correct the things that are unusual about her because those are the things that make her distinctive. She’s also very aware of her own proportions, very aware of that bobbed hair, that sort of elongated Art Deco vest and pose, and she was leading me into that. So I heightened it a bit in the painting. I didn’t even know when I was starting out how much I’d do. But it was one of those pictures where I liked everything about it. The composition should have been awkward but it was very balanced. In a way it was a commission but not a commission at the same time.

She had suggested it, but she’d said to me, ‘I just want someone to do a painting of me because I’m so used to seeing pictures of myself at this stage of my life that are not me. They’ve been decided by someone else, they’ve been commissioned by someone else, they’ve got other people’s agendas all over them; whether it’s the stylist or the advertiser or the editor or whoever it is, there’s someone else directing it and turning me into someone else. I don’t have any pictures of who I actually am at this stage in my career where my currency is my face.’ She said, ‘A painting might be the only way to do that.’

That was about ten years ago, just before the explosion of Photoshop. It was a really neat little encapsulation of what a portrait should be and what it can do that the photograph can’t be trusted to do.

SG: You have also painted the many sides of Sienna Miller – she was obviously a very willing sitter.

JY: Sienna’s interesting because she’s a chameleon. She’s a very brilliant actress and she’s very good at becoming different people, but it’s her deciding to do it and not somebody else, whereas some fashion models are just too brilliantly bland and completely turn into something else, and you don’t notice who they are at all. With Sienna, the difficulty is that she’s so good and quick at turning into someone else and she can go from being serious to beauty queen to being so raucously funny that she’ll make you fall about laughing. So it becomes about how to pin her down to who she really is and who she is being on a certain day.

It’s interesting painting people like that, but it sometimes becomes a series of works because no one picture tells the whole story. Maybe that’s true of all of us; maybe it is impossible to get everything about someone in one image. It’s difficult to shoehorn that much in. But I do think that you get a greater opportunity to put more information about different aspects of someone’s personality into a painted portrait than you would into a photograph because it is built up over a period. It is an assimilation of lots of different images in your mind, which are created over time.

SG: And is it the same with self-portraiture? You’ve made some self-portraits, but not many. Is that a conscious decision or do you just feel that there are too many subjects out there that you don’t need to use yourself as a model?

JY: For a long time I tried to do self-portraits and ended up doing the classic thing of making paintings that looked vaguely like me but maybe more like a relative frowning, staring, concentrating very hard, looking a little constipated, and of course reversed because it was reflected in the mirror. So people would say ‘Uh, who’s that?’ From time to time, but not very often, I get a big bunch of photographs I’ve taken myself with a digital camera and just say to people, ‘Which ones of these look like me?’ If there’s a bit of consensus, I think ‘Okay, next time I want to do a portrait, I’ll use this one.’ It’s a bit of a cop-out really – you’re abdicating a bit of the editorial.

I’m interested in the things that single out a person and define them, and what happens underneath the self, the way the personality comes out through their eyes and how they speak and how their face moves. I’ve seen a bit of it more recently in myself. I had the horror of doing a television interview and then watching it, having to look at the way all of one’s own stammers and strange ticks are on show.

Normally the image you see of yourself is the one looking back in the mirror in the morning, when you’re looking slightly overtired, pouting a bit, sort of sticking your neck out to look a bit thinner, and reversed. So it’s very different from the way anyone else sees you. Whether you’re looking at a photo of yourself or just looking in the mirror, you’re not animated, and even if you are animated, you don’t know yourself well enough to know which expressions are genuine ones and which aren’t. You can’t sift through that.

SG: To end I want to ask you about the portrait that you’re working on at the moment, which is a painting of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl and activist who was shot and almost killed. It’s a very challenging subject. You’re portraying a girl who’s fifteen years old who has had this life-changing experience; but she’s very innocent about the world. There are so many layers to her and to her image, it must be a very difficult portrait to make.

JY: Yes it is. It’s complex because you’re not just dealing with someone who has experienced much more than most fifteen-year-old girls – although coincidentally my sister had a brain tumour at the same age and also had her movement affected in the same way, so talking to Malala reminds me of that time many years ago. She has been through so much and has been so brave; utterly courageous, fearless, confident and clear thinking throughout this horrendous traumatic experience. And now she is rebuilding her life in a completely different part of the world. She was taken with her whole family from rural Pakistan to a place in England, which must be so alien.

So you’re dealing with someone with an extraordinary story and so much more packed into their lives than you would normally expect to see on the face of a teenager. On top of that, you have to take into account the fact that she is this hugely iconic figure for different audiences around the world. You have to be sensitive to what she represents in her home country, where they are much more conservative than we realise. I think she has single-handedly helped more than years of politicking and foreign policy to convey to a younger generation that they need to recognise cultural differences, to see what needs to change in the world and what can be done to make those changes.

The portrait is partly being done to help raise awareness and funds for Malala’s foundation, which is educating girls not just in Pakistan but all over the developing world. She has been through this herself and now she’s had all this additional responsibility thrust upon her.

When you are with her, you are aware that you’re talking to someone who believes in it all, and who will probably have an important political role to play in the world over the long term. But she is also just a fifteen-year-old girl who should be allowed a little bit of childhood. She’s beautiful and charming, charismatic, serene and wise, but also very fragile. It’s not just the knowledge of what she’s been through that makes her seem fragile. She is quite small physically, but in a way that is part of what makes her power all the more tangible, because she exudes something very special.

I am still trying to decide how much to do to the painting, and maybe I won’t do too much. I want to leave some of the clothing out because I want to have this sense that she’s a religious icon but not necessarily an Islamic one. What I think is most important to convey is that she is a representative of humanity as a whole, irrespective of faith, and, if things progress in the right way, a huge force for good. I think she’s aware of that as well, but that of course adds an extra pressure to everything.

She’s surrounded by people who all want to give her advice, mostly for good reasons, but also for some self-interested ones, so it’s very, very difficult for her. I think we’d have trouble treading that sort of path even at our age, let alone at hers when your experience of the world is so limited.

Whatever happens, this is an interesting moment in her life to record who she is and to have the quiet contemplation of a painted image rather than press photographs. After looking through previous photographs of her used in the media, she said, ‘This isn’t really me’, and all of her family said the same thing. So I am trying to create a slightly ambiguous, enigmatic image that people will project certain things onto, but I want to start with whatever is there at its heart, to be absolutely truthful to Malala.